Education for Liberation

A Critical Look Into How Power and Community Manifest in the Work of Student Organizers

Olga P. Guerrero, Lilly Le, Jin Yoon

Disclaimer: This project was completed for pedagogical purposes for an undergraduate sociology course at University of Chicago. While we are sharing results from our mini-project with the public, it is important that readers understand these are NOT findings from a human subjects research project intended to contribute to generalizable knowledge.

All images belong to UChicago United.

Research Question

The modern day university touts itself as a bastion of liberal education, and in recent decades has been considered a necessary step towards a successful and self-fulfilling life in an ostensibly credential society. Yet critical research has continuously demonstrated the promised link between a university degree and individual social and economic success is but a tenuous connection and, in fact, primarily benefits and favors the elite class of society. In a wave of resistance, the long-standing lineage of student-led movements on college campuses continues to directly challenge the institutional workings of higher education. At the University of Chicago, UC United’s #EthnicStudiesNow campaign has been organizing towards an Ethnic Studies department that is rooted in the histories of past student organizers, and centers an abolitionist framework. Given the importance of their radical work for liberatory education, we ask:

Why do students of color join and stay in the struggle and movement for ethnic studies at the University of Chicago?

ONGOING FIGHT

To situate the #ESN campaign in the broader conversation around ethnic studies right now, we wish to highlight that the fight for ethnic studies is an ongoing struggle that permeates all levels of American education, at both public and private institutions. Recently especially, the murder of George Floyd and resulting waves of protests against racial injustice has sparked dialogue around educational reform to include mandatory ethnic studies curricula, and we have seen student and faculty coalitions demand for establishment of Ethnic Studies programs and departments at their respective institutions.

#EthnicStudiesNow

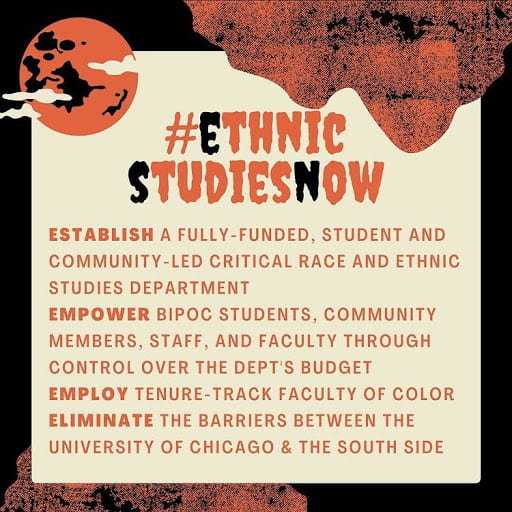

The #EthnicStudiesNow, or #ESN, campaign at UChicago was started in 2017 to establish a department for the Critical Race and Ethnic Studies (CRES) department at the University of Chicago. Some of the structural limitations that come without a department include lack of committed faculty, dearth of critical race theory or analysis in classes, and simply an absence of CRES classes in general. #ESN is part of the ongoing fight for ethnic studies nationwide as it seeks to establish department that will generate a new model for the university, one that champions community safety, care, and collective liberation through education.

Literature Review

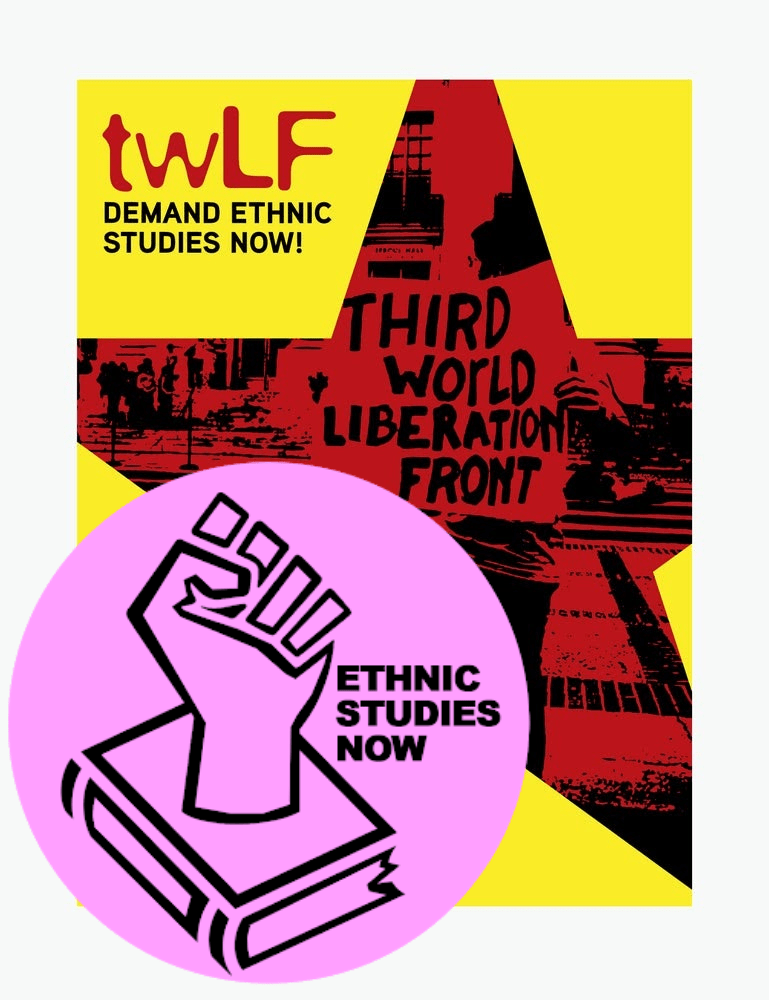

The ESN campaign works directly in the lineage of students movements of the past. For this reason, we found it necessary to first situate our study in the context of demands made by the early ethnic studies coalitions. From the Third World Liberation Front at San Francisco State University to the Lumumba Zapata Coalition at UC San Diego, ethnic studies has always been a field born from and into struggle. These past student movements exemplify that ethnic studies is larger than a more diversified curriculum, but about truly challenging the oppressive power structure of the university through mobilization and organizing.

We build on the current literature surrounding knowledge institutions, and institutional change as our concept dimension. We build off of Paul Bush’s definition of knowledge institutions, as sites of “socially prescribed patterns of correlated behavior” that describe “the nature of industrial societies with fundamental implications for the future shape and role of higher education”. Knowledge institutions are characterized by the creation and maintenance of knowledge societies, “where knowledge, information and knowledge production have become defining features of relationships within and among societies, organisations, industrial production, and human lives”. Further, Steven Loomis and Jacob Rodriguez’s description of institutional change at its most basic includes the “supplanting of the old model of production with a new one” and the transformation of “the value structure of the institution”. In our study, we take a close look at how student organizers of color at The University of Chicago seek to uproot the current processes for knowledge production in order to reimagine education and push for institutional change—change that they conceptualize through a discussion of what community and power mean to them.

Why Our research matters

Currently, the scholarship surrounding ethnic studies and critical studies lacks a robust understanding of why student organizers choose to involve themselves in this work. This means that the liberatory knowledge, theory, and practice that is produced on the ground by student organizers who have organized against the university and created their own understanding of its workings and power–the knowledge that is not often included in published scholarship nor treated as legitimate, critically nuanced analysis of the university–must not only be uplifted, but made central to any meaningful, rigorous examination of the university.

Methodology

Our study aimed to explore why students of color join ESN. Building on Dr. Masta’s Tribal Critical Race Theory, we define “objectivity” as a primarily Western perspective and reject the idea of objective research. We zero in on the experiences and ideas shared by six students through semi-structured interviews to uplift their knowledge. We conducted thematic coding and identified 2 major themes that are central to student organizers’ experiences within ESN.

Approach

Exploratory

Data Method

Semi-Structured Interviews

Analysis Method

Thematic Coding

Findings

2 Major Themes

Findings

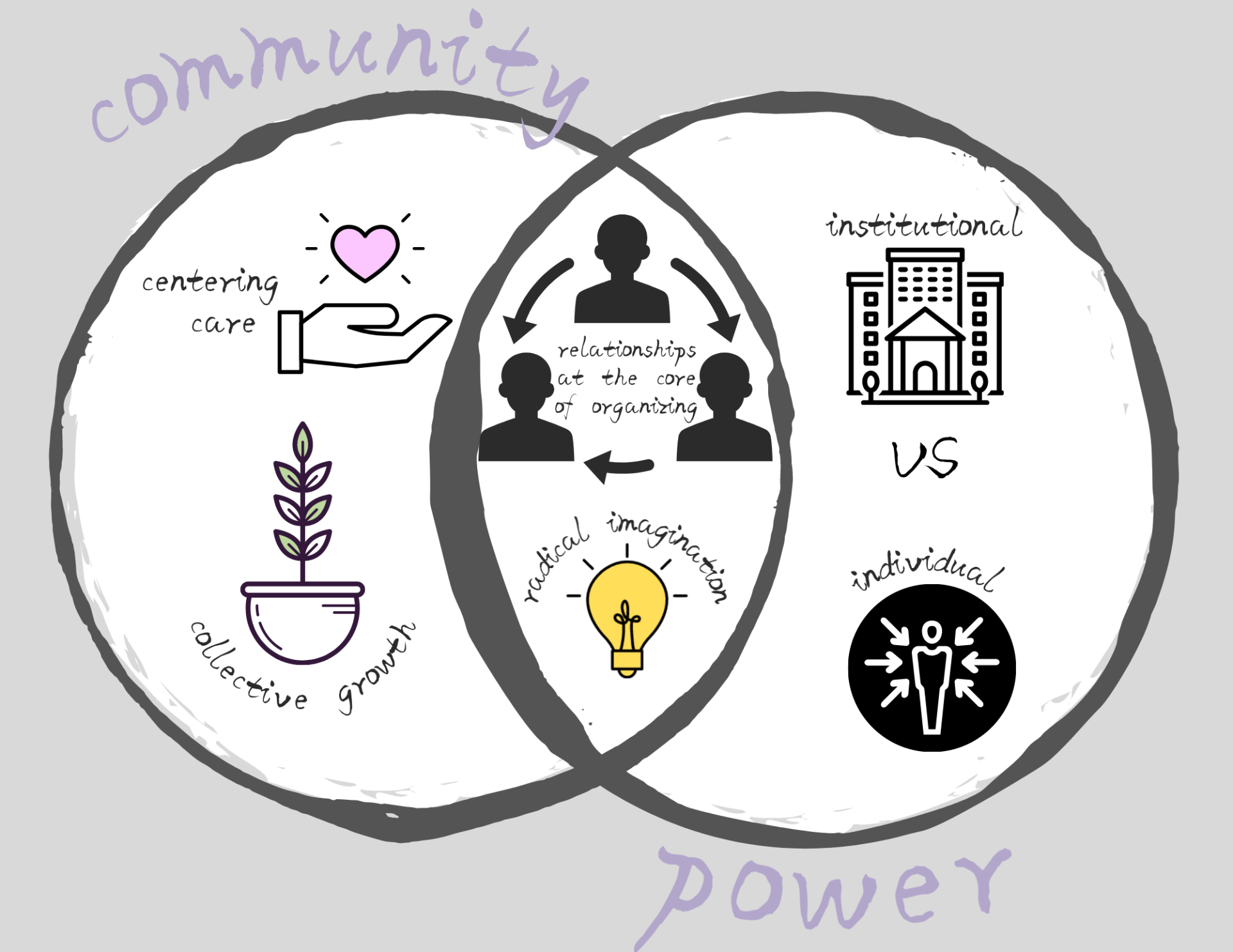

We found that the main forces that led students of color to join and stay in ESN were community, power, and what lies at the intersection of the two. On its own, community is defined by care and collective growth. On the other hand, students found power varies depending on whether it is at the institutional or individual level. For instance, institutional power at UChicago is rooted in money and resources. Power at the individual level can be found among student organizers pushing for institutional change. Community and power together form strong organizing relationships and generate the kind of radical imagination that creates change. We will now elaborate on these themes.

Community

Our participants discussed experiencing a lack of community and feelings of isolation at UChicago prior to joining ESN. Connections lacked meaning because they tended to bond with people simply due to proximity. Through ESN, student organizers see community as purposeful relationships that are built on shared values and practices such as care, accountability, and collective learning. Community in ESN means being vulnerable with one another, celebrating each other, and holding others accountable.

Quote

“…[it’s] being able to share a space with people who care about me, who want see me grow, who hold me accountable..and share the same values about care and accountability and about..the world we want to see…” – Oreo

Community + Power

Student organizers discussed how these two concepts overlap. For example, through the community built within ESN, students are able to learn from each other and generate knowledge that is produced horizontally, where everyone is considered equal, and there is no single person teaching. The horizontal power dynamics found in community generate the radical imagination that makes big change seem possible. Ultimately, we found that our participants consider community to be fundamentally self-empowering and that relationships themselves are power.

Quote

“I feel like community at its core is about an almost cathartic type of relationship building. Something that I think is empowering to the individual but also something like the community as a whole is creating that. It’s also powerful.” – Naruto

Power

Because of ESN, student organizers believe power is not inherently bad. To them, power is generally defined as the ability to make decisions and create change in one’s self interest. It is not something that is earned or bestowed upon someone; rather, power is generated in oneself and within community. Through ESN, students now understand power to be something that all people desire to have and that is key to one’s self-determination.

Quote

“…if you think of power as like self interest, then we all have our own self interest, right? So power is not bad, because our self interest will always align with wanting more power…just to live.. to have agency..as a person and decision making power and all that…” – Tsukki

DISCUSSION

Cyclical Mechanism

We found the primary force that encouraged the student organizers to stay in the movement and fight for transformative change was the fundamental understanding and realization of the power within their community. While pushing the boundaries of what we imagine higher education to be and grappling with questions of “What is community? What is power?”, the young organizers of color found that in fact, community is power, and power is in community, pointing to a cyclical mechanism where students find personal empowerment in organizing community, and the community, in turn, builds more collective power.

What Next?

Organizing is not a space meant to obtain individual power, money, or status. The work of organizing exists because communities identify an issue, and work together to tackle it. The student organizers we interviewed consistently invest their own time, energy, and resources into ESN not for clout, but because they recognize that a revolutionary future means working with one another and supporting each other.

In a world where our minds, bodies, and souls are over-policed and hyper-surveilled, we encourage you to also reflect and consider: What does community feel like to you? What does power feel like to you? If you are left feeling hopeless and lost, we urge you to seek out organizing spaces in your own area. How will you join the movement for a liberatory future?

CONTACT US

Fill out the contact form for general inquiries about this project. You may also reach the authors of this project individually at email addresses listed below the form. Feeling inspired and want to join the #EthnicStudiesNow campaign? Scan the QR code to get involved!

Email:

Olga Patricia Guerrero

Lilly Le

Jin Yoon

Works Cited

Bush, Paul D. “The Theory of Institutional Change.” Journal of Economic Issues 21, no. 3 (1987): 1075-116. Accessed November 29, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4225919.

Loomis, Steven, and Jacob Rodriguez. “Institutional Change and Higher Education.” Higher Education 58, no. 4 (2009): 475-89. Accessed November 29, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40269197.

Lumumba-Zapata Coalition. “Lumumba-Zapata College: B.S.C-M.A.Y.A Demands for the Third College, U.C.S.D.” March 14, 1969. Record # b4814455. Special Collections. UC San Diego Library, San Diego, CA.

Masta, Stephanie. “Challenging the Relationship Between Settler Colonial Ideology and Higher Education Spaces.” Berkeley Review of Education 8, no. 2 (2019): 179-94.

Third World Liberation Front, “Strike Demands.” January, 1969. Location 1:2 twLF box 1 Folder 2. Ethnic Studies Library, Berkeley, CA.